By Ven. C. Nyanasatta Thera

At the very beginning of our discussion, we must state concisely the Quintessence of Buddhism. Though the Teaching of the Buddha may be studied scientifically as a mental science, it is more like philosophy, and still more like psychology and ethics, hence it is sometimes called Psychological Ethics. Buddhism may also denote a form of civilization, culture, man and other things, for in the far off days when it arose, all these departments of study were not yet differentiated and they were called “Dhamma’ or ‘Dharma’. For the practical purpose of our present exposition, we shall treat Buddhism also as one of the great world religions, using the word ‘religion’ in its earliest meaning as ‘respect for truth and law’. However, in order to avoid confusion and controversy at the very beginning of our exposition, we shall use the term ‘Dhamma’ rather than a Western concept which is objectionable to many students of the Buddha’s Teaching. The term ‘Dhamma’ throughout our discourse stands for the cosmic and moral law that was revealed to the Buddha in the night on his Enlightenment. Dhamma, then, means the moral and philosophical teachings of the Buddha and his immediate disciple. The sacred books providing our knowledge of the Buddha-Dhamma are the Early Pali Text Books, the scriptures called the Tipitaka, and the Commentaries in the Pali language.

THE BUDDHIST

A Buddhist is one who takes refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Order of the Disciples (sangha), studies the Teaching and endeavor to follow the Dhamma in his daily life. ‘To take refuge’ means to put one’s trust in the Enlightened One, his Teaching and the Order, to accept the guidance of, and listen to the advice of the Buddha, his Dhamma and the Order of Disciples. In order that the true Buddhist may be able to translate the printed Word of the Buddha – Dhamma into practice in daily life, he must first study, understand, investigate, appreciate and love the Teaching. This study, comprehension, appreciation and love of the Dhamma arises to unshaken faith, or rather confidence, in its truth. Confidence arises from application. Every step forward on the Path of the Dhamma gives the student confidence, conviction, and faith in the Teaching.

THE BUDDHA

The Buddha, as a historical personage, is the Enlightened and Compassionate Teacher who by his own effort has discovered and first realized the Truth called the Dhamma, has the ability to reveal the Dhamma and to lead other intelligent beings to the realization of the Truth taught by the Buddha. The Buddha is the ultimate source of our knowledge of the Dhamma. As synonymous with ‘Buddha’ we have other terms:- Tathagata the Perfect One; Bhagava – the Blessed One; Sambuddha – the Perfectly Enlightened One; Sammasambuddha – the Perfectly All Enlightened One; Sakyamuni – the Sage of the clan of the Sakyan ; Sugata – the Happy One, or the Accomplished One. In later Buddhism we have many more terms as synonyms of ‘Buddha’. A real Buddhist does not refer to the Enlightened One as Gotama or Gautama, for it was the non-Buddhists and the haughty Brahmins who called him by family name. The term ‘Buddha’ is not a proper name but a title of honour meaning: The Awakened One; hence we prefer using it with the definite article, in order to forestall any possible confusion to a metaphysical principle.

In the Early Pali Books the Buddha is treated as a historical personage born at Lumbini, a place that lies within modern Nepal. Though the exact place of birth is known, there is a disagreement between the scholars of the East and those of the West about the year of birth of the Buddha. According to the Ceylon Chronicles, he was born 2,580 years ago, that is 624 B.C. But students of History have found that the number 218 years after the passing of the Buddha as the year of the consecration of Asoka must be wrong, and hence the Buddha must have been born about 60 years later than indicated by the Mahavamsa, hence they give the date of the birth of the Buddha a 564 B.C. This fact may startle the student; but we must call his attention to the truth that the same is the case with the birth year of Christ, which some scholar put 30 years later, and even the Church admits that it might have been at least three years later than the year established by Church Council. As the Buddhists have not yet authoritatively fixed the year, we have different dates for all events in the history of Buddhism, and the student must not worry about this. The Buddhist year does not coincide with the Western New Year; all dates are calculated by giving the number of years of the reign of the kings; the same kings might have died at the beginning of the year, and at times rival kings might have ruled at the same time, hence these counting results in the difference. We shall adhere to the data given by the Ceylon Chronicle and say that the Buddha was born 624 B.C. or just 2,580 years ago and hence lived and taught in the sixth century before our era. He was born as a prince, and it was in his 29th year that he renounced the life of pleasures and became a homeless mendicant and religious student. From that time on ward till the age of 80, the Budha spent all his time living in the many monasteries and hermitages or journeying during the fine season from place to place in the various ancient republics and kingdoms of North India, the present Nepal, Bihar, Bengal, Uttarpradesh and the adjacent regions. The Word of the Buddha and his immediate disciples have been handed down in Pali, a beautiful language similar to Sanskrit, and the tongue most probably spoken by the Buddha and widely understood all over North India at that time.

THE DHAMMA OR THE TEACHING

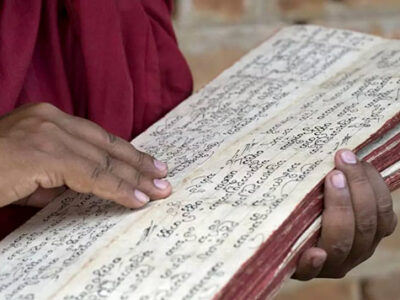

The Dhamma is the Ethical and Philosophical Teaching of the Buddha, the cosmic and moral law governing this world and our life, realized and revealed by the Buddha to his immediate disciples. It was the oral teaching of the Buddha that was soon arranged into groups of related topics of similar length; and these groups or the larger units of the books were fixed and named the “Collections”, or “Pitakas” and the whole body of these Collections came to be known as “The Three collection of Scriptures’, the Tipitaka. The Three Collections are called “The Vinaya” or the Collection of Rules and Regulations governing the life of the community of monks’ ‘Sutta’, or the Collection of Discourses on the Dhamma; ‘Abhidhamma’, or Philosophy, literally, Higher Doctrine. After several Councils – Sangayana, or Sangiti – where the orally preserved texts were recited, all the Pali scriptures were written down on hard palm leaves – one of the lasting materials for writing and these books bearing the Word of the Buddha were guarded all these twenty centuries as the most precious possession of the nations that called themselves Buddhist. At present the Word of the Buddha is handed down not only in printed books and on palm leaves, but also on marble slabs in Burma. The earliest records expressly referring to the Buddhist scriptures are the Pillars and rock-carved Edicts of Asoka, dating from about 240, or 180 years (according to modern calculation) after the passing of the Buddha. Some Buddhist kings are said to have had whole books engraved on copper plates or even on plates of gold, for no baser metal was thought good enough to bear the Word of the Enlightened One. Beside the Pali Books there are Buddhist scriptures in Sanskrit and translations into Chinese, Tibetan and other tongues from the original source; as all the earlier records agree in essential historical date and facts of the life of the Buddha and the Early Teaching, this agreement proves that our Pali Books reflect the historical teaching and not compositions made in Ceylon by monks, for all the books refer to conditions of life and geographical and historical facts in North India of the sixth century, with not a single reference to Ceylon, not even to Asoka, who sent the Dhamma there.

THE THERAVADA

The form of Buddhism which has been handed down to us these 2,500 years in the Pali Scripture and is known and practiced in Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Chittagong in East Bengal is called ‘Theravada’, that is to say the Teaching of the Elders, the immediate disciples of the Buddha. The core of the Theravada is the historic teaching of the Master; but the word of the Chief disciples, other great disciples and other interlocutors of the Buddha and his disciples is side by side with the word of the Buddha. At times it is one of the great disciples that expand the terse formulation of the Master for those who find difficult to grasp the meaning of the too concise exposition. Hence it is not quite accurate to say, as is often done, that the Tipitaka, or the ‘Three Collections’ of the Teachings of the Buddha, contains only the Word of the Buddha.

In process of memorizing, writing down and explaining the Teaching, perhaps a new frame giving the occasion and setting of the discourses was added to the Early Message and many legends, myths and much folklore entered into the books. Pious stories appealing to the imagination of the more naïve listeners were included too, a useful aids in preaching the Dhamma. About nine hundred years after the Buddha, great Commentators like Buddhaghosa, Dhammapala and others, completed the work begun in Buddha’s time, namely explaining the true meaning of the Early Scriptures. Thus we have the Pali Texts, the Commentaries and Sub-Commentaries, all in Pali. Then there are the Mediaeval Compositions and Compendia and Chronicles of the Sinhalese, Burmese and other scholars, composed either in Pali or in the national languages, all the books being invaluable aids in the study of the pristine Teaching. This process of adding new books to the extensive Buddhist literature continued even in our days, especially in Burma. And as Buddhism spreads all over the modern world, new approaches to the classical Pali literature are tried, and new methods of exposition necessitate ever fresh additions to the enormous output of Buddhist scholarship. In our own lifetime the Theravada has obtained footing not only in the new Eastern lands like Malaya, Singapore, parts of Vietnam, in Nepal, in many new centres in India, mainly those revived by the Maha Bodhi Society, but also in many Western lands, mainly in America, England, France, Germany, and still many more countries of the West.

THE MAHAYANA

It appears that soon after the passing away of the Buddha, and perhaps even in the Teacher’s own lifetime, some erring disciples formed different conceptions and formulations of the Dhamma. While the Master lived, such erroneous views were soon corrected. But after the passing of the Enlightened One, in process of time, there arose a new trend or several new trends in the Teaching, calling themselves, or being called by others, by various names, but later on were known under the collective name ‘Mahayana’. i.e. the Great Career or the Great Course, sometimes meaning also ‘The Great Vehicle’. Long before the term ‘Mahayana’ was coined, there were various Schools of Buddhism, as for instance the Sravastivadins, the Vaitulians, the Mahasanghikas and others.

According to the information given in the Pali books, the principal source of departure or secession from the main body of disciples was the relaxation in discipline and reluctance of refusal to submit to the disciplinary rules of the Vinaya. i.e. the regulations for the guidance of the Buddhist monks, or bhikkhus, But the adherents of the Great Career to Enlightenment – Mahayana – have a different story to tell, namely the intellectual and spiritual inferiority, that is to say the inferiority in intellectual and spiritual attainments of those who were the exponents of the rigorous discipline. Therefore the allegedly more progressive teachers began to call the conservative bhikkhus backward, and nicknamed them ‘Hinayana’, i.e. the followers of the Lesser Vehicle of the Inferior of Lower Career or Course. When too many learned Brahmin coverts became Buddhist monks and the retraining power of the Budha and truly saintly Elders was no more felt or respected, extraneous philosophical ideas and new metaphysical concepts and conceptions began to enter the Teaching. Skill in dialectics, that is to say, dialectical dexterity in enunciating the new ideas as the ‘esoteric’ or secret, doctrine of the Buddha himself, who had withheld those doctrines from the Elders, the Theravada disciples, owing to their inferiority in comprehension, succeeded in convincing some students and supporters of the alleged superiority of the new trend. Inspiration, poetical talent and mysticism began to weigh more than one’s own self-realization of enlightenment and liberation, the real goal of the Dhamma. And seeing the new effusion of productivity and creativeness, perhaps also flushed with the pride arising from applause and large following, the leaders of the new movement began to despise the sober self-effacing virtues of the monks of the Pali tradition. They began to use Sanskrit as their literary language, called their new system the Mahayana, the Great Career, the Higher Course to Enlightenment, and jeered at the parent stem of Buddhism, calling the Theravada ‘Hinayana,’ i.e. the ‘Lesser Career’, the Lower of Inferior Course of Training. There is bitter accusation of the opponents on both sides, for neither side pared its critics.

After more than two thousand years of complete separation, the two great Schools of Buddhism are inclined to come together again. Buddhist scholar have now realized that the Hinayana referred to in the controversies is not the Theravada, but some long extinct sect of Buddhism, so that the term of reproach, ‘Hinayana’, is not applicable to any form of Buddhism living. As the opponent has been dead all these fifteen hundred years, the old controversies are slowly becoming a closed chapter in the History of Buddhism.

Though for the erudite Buddhist many points of the old controversies continue to be valid, there is a new trend noticeable in the whole Buddhist world, and also in Ceylon. After more than two thousand years of complete and hostile separation, many Buddhist scholars especially among the intellectual laity feel the need for unity among the Buddhists. These Buddhist Liberals now emphasize the points of agreement rather than those things that led to the split. The main point of difference had always been that, while the Theravada monks adhered to the ideal of the Arahant, that is to say, the enlightenment of the disciple, attainable in his lifetime by following the Noble Eightfold Path of virtue, contemplation and self-realization of Deliverance of Enlightenment, or attainment of Nibbana, the Mahayana rejected this ideal as inferior, and proclaimed the ideal of Buddhahood. i.e. everyone becoming an All-Enlightened Buddha, as the sole worthy object of human striving. Thus the followers of the Mahayana consider themselves all potential Buddhas of Bodhisattas, as the beings aspiring to the highest enlightenment are called.

It is only in our lifetime that scholars have realized, or begin to realize, that the ideal of the Bodhisatta is now really appreciated in the Theravada countries too, and that the popular form of Buddhism taught in those lands is more akin to the Mahayana than was the long extinct ‘Hinayana’. Philosophy and learning are not despised by the modern monks of the Theravada countries, and there are very few among them today who earnestly strive to attain Nibbana in their own lifetime, but most of them, like the priests of the ‘Great Career’ are more like clergymen, ministers, preachers or teacher than the hermit bhikkhus of old. Hence there is no reason why one should despise the other and feel superior or inferior to those of the other School of Buddhism. If the Mahayana Buddhists study a little of the more rational Pali Buddhism to strengthen their position at home, and if the Theravada Buddhist practice better the Bodhisatta Ideal and often forgo their own pleasure for the sake of doing good to others, we shall have an ideal synthesis of World Buddhism.

Largely because some of the principal Mahayana lands, China, Tibet, a part of Korea as well as Vietnam have embraced a new ideology and do not now really count as Buddhist lands, and because Buddhism in Japan has much weakened after the war and years of occupation, some leading Buddhist now fully realize that if the Dhamma is to survive the increasing pressure of new materialistic ideologies and alien religions, and triumph in the whole world as the universal Teaching and the only acceptable Philosophy of the modern man, the Buddhists must feel united in their loyalty to the Enlightened One, always stressing the Early Teaching and discarding many of the later accretions that are now mere ballast and the very things and points criticized by the intellectual Buddhists and by the non-Buddhist critics of Buddhism.

THE SANGHA

The Sangha is the Order of the Disciples of the Buddha, the Community of those who have realized the Truth first proclaimed by the Buddha or who are seriously striving to realize it and who by example and precept teach the Dhamma. In the Pali Theravada usage, Sangha denotes only the Bhikkhus, i.e. the members of the Order who have received the higher Ordination called Upasampada. Novices and candidates for ordinations do not yet strictly belong to the Sangha, though the new tendency in the West is to count also the laymen to the Order.

THE ESENCE OF THE TEACHING

The Quintessence of the Buddha’s True Doctrine is the Four Noble Truths, the four propositions governing all the Scriptures. The huge volume of Buddhist Literature is but the restatement, amplification and application of the Basic Dhamnma.

- All conditioned existence, especially human life and the objects of our cognition, striving, craving and grasping all the manifold objects of our experience are unsatisfactory. Life itself is a conditioned process initiated by conception, followed by birth, pain, sorrow, grief, lamentation, disappointment, despair, union with objects we hate, separation from what we love, old age, disease and death, which is again followed by a new rebirth according to our actions, either in heavens, on this earth, or elsewhere. This is the Noble Truth of suffering. Though this proposition is so repugnant to, and so dreaded by the opponents and critics of the Dhamma, the Buddhist calls it noble. The statement of this Holy and Pure Truth of Suffering makes the student pause and reflect; and it may lead to liberation from a new individual life and from the entire manifold suffering connected with life, or synonymous with life.

- All the various forms of suffering and all forms of individual life are conditioned or caused by Craving. This craving for the continuation of our life and for a new life and for the objects of sense experience is nourished and sustained by ignorance or delusion. This ignorance and delusion about the true value and nature of life and the world make man crave for continued life in Heaven or a future rebirth as a powerful king, a great politician, a Leader of a new Movement or School of Thought, or a great personage in some other sphere of life. Instead of learning all about the real nature and value of life and things or conditions, we always crave for new objects which, when attained will not satisfy us. We move from place to place, from country to country, learn many new languages in order to be able to live with other nationals in the hope to find our true home and perfect satisfaction among them, but all in vain. Meanwhile one individual existence ceases, our life span ends, and then it is this very craving, never to be appeased by gratification that links one life with another. This occurs, among human beings, in the moment of conception, the fructification of the ovum-cell by the sperm-cell. By the craving–force of a ding being that seeks its own affinity, or congenial conditions for a new life, the two cells become united, and thus a new life germinates in a mother’s womb. This process of conception, dependent on three factors, instead of the two admitted by Biology, becomes clearer if we use the illustration of the last spark of an extinguishing fire which kindles new fuel according to its strength. The teaching of craving as the condition, or cause, of new existence is called the Noble Truth of suffering.

- By attaining true intuitive insight and penetrating vision as a result of systematic training in the patient application of mindfulness and concentration of the purified mind, the real nature of life and the world with all its false attractions, delusions and craving or grasping, is understood, and with the cessation of craving, all suffering erase. This proposition of the perfectibility of man by his own effort, under the begin guidance of the Buddha – Dhamma, is called the Noble Truth of the Cessation of Suffering.

- The Path, or Method, that leads to the self-realization of the end of suffering by the Conquest of Craving for the pleasures of the senses, Craving for continued life, and Craving for self-annihilation after death, this Method of Training for Enlightenment and Liberation I called the Noble Eightfold Path. The eight links, or factors, of the Path may be summed up in the three divisions as: moral life, culture of the mind, and intuitive insight, or wisdom. For a lay student the first part, the path of virtue and morality, is concerned in the Five Percepts; to refrain from killing or harming living sentient beings, from stealing, from unlawful sex-relations with one belonging or promised to another, from telling lies, and from using intoxicating drinks and drugs that cause loss of mindfulness and moral restraint, lead to moral recklessness, and retard one’s progress on the Path to Perfection and spiritual liberation. It is by treading the path of self-control, spiritual culture and wisdom that the student of Buddhism applies the most in fact the only effectual method of bringing about the end of all ignorance, delusion, craving and grasping. This is the Noble Truth of the Path that leads to Cessation of Suffering.

SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT

Moral life, self-control, or self-restraint leads to a peaceful, or placid, disposition of the mind to freedom from remorse, worry, and all agitation, restlessness and uncertainty. With such a placid disposition it is possible to devote the best moments of the student’s leisure to the practice of mindfulness and concentration. This culture of our latent spiritual insight or intuitive penetration to the real nature of things as they are, independent of the value we place on them in our delusion, with our mind biased by craving or ill-will. When we see all the components and aggregates of our existence and experience, our life and the objects of our cognition and craving, as impermanent, unsatisfactory and fraught with suffering, not self-existing, not self-contained entities or constituting one’s self, i.e. an impersonal, then all delusion and with it all craving and grasping cease. Only then liberation from all sorrow is attained and spiritual enlightenment achieved. The individual who has realized this spiritual perfection or holiness lives his span of life free from all selfish desires. He devotes himself to the service of others; he is a guide of his fellow-men who are striving for the blissful state which he has already attained.

When such a holy one, be it a Buddha or an Arahant Saint, passes away, there I no more rebirth for such a perfected Saint, a Saint in the highest sense, because his affirming and life-linking craving had been extinguished long before his physical death he enters the Nibbana without a substratum of becoming. The term Nibbana, or Nirvana, is used for the state experienced by the Buddha and the Buddhist Saint from the moment of self-realization or Enlightenment to the final passing away of his mortal frame. Nirvana, or Nibbana, literally means freedom from craving and delusion, ‘the blowing out’ of the fire of lust, hatred and delusion. Positively it can be called Enlightenment and bliss unperturbed by any external contingency.

The self-realization or actualization of this condition is the ultimate object of all the striving of every genuine Buddhist. Some earnestly hope and strive to attain Nibbana in this very lifetime; others fervently hope to achieve the task of liberation in the next life or in one of the lives that lie ahead of them. When Buddhist Teachers attempted to explain logically the intrinsic nature of Nibbana without themselves attempting to fulfill the necessary conditions for this achievement, they disagreed, as doctors often do, and split the Buddhist World of those far-off days into opposing camp. They also created what is now called ‘aversion to Nibbana.’ The student must always bear in mind that Nirvana is a matter of self-realization and that no argument can either bring it nearer or make it a condition of craving or aversion.

In order that the student of Buddhism may become an effectual witness to the living and ever-fresh flourishing Buddha-Dhamma, he must not to be contented with mere intellectual appreciation of the Teaching, and leave his higher spiritual faculties to starve and stagnate. Neither must be rest satisfied with his present state of life, the continuation, or rather repetition, of which he tries to secure in the future by some small charitable act. The Buddhist who had learnt the Dhamma piecemeal and uncritically in his youth, must at his higher level of education relearn the Teaching in a ‘Refresher Course of the Dhamma’, and only then he will feel inclined or even impelled to practice it in his everyday life. Instead of glorifying the conquest of nature by physical science, he must strive to achieve the conquest – not of Mount Everest, of some as yet un-scaled peak or even of the moon and some of the planets but of the blemishes of his own nature. Some faint–hearted men hold the defeatist view, unworthy of the disciple of the All-enlightened One, that man of his own strength cannot achieve this lofty ideal of self-conquest but needs and extraneous superhuman aid or Grace, or a Saviour. The mere existence of the Law, even of the Good Law of the Supremely–Self–Enlightened One, so long as the Law and its statement is merely stored in books, merely memorized and then preached, surely cannot bring the Deathless state. But when the Noble Law of the Perfect One is once well studied, comprehended, appreciated and loved, then faith, or confidence based on understanding, the seed out of which sprouts the progress on the Way to Perfection, achieves what ‘Grace’ or ‘Saviour’ may be supposed to achieve elsewhere.

REALIZATION

This is a period of Buddhist Renaissance. In the past centuries, the eclipse, or the dark ages, in the History of the Buddha – Dhamma, people actually created a defeatist atmosphere, declaring that the ‘Gates to the Deathless’ (Nirvana) are now definitively closed and the Buddhists have to await the advent of a new Buddha. Now all this talk has proved wrong, for all over the Buddhist world, the ‘expanding universe permeated by the Buddha – Dhamma’, is seen new life and a strenuous effort in the practice of the spiritual conquest of self. Though the Historical method, or the so-called Higher criticism, once really startled the students of Buddhism and threatened to take away all their faith in the Dhamma, now the Buddhists give the life to the scholars. But let us be quite honest about the true state of affairs; the understanding of the Dhamma was not inherited even by the born Buddhists. Just like the alphabet and the multiplication table, it has to be learnt a new by all of us. The ideal of the Buddhists is the individual who is truly restrained, disciplined, and spiritually liberated, and he is not born as such. Each student of the Dhamma has to learn and acquire the restraints and discipline, and must individually strive and struggle for spiritual liberation and enlightenment.

In a stirring exhortation of the Buddha to Cunda, one of the ‘eighty foremost disciples of the Blessed One’, the Perfect One says:- “Truly, Cunda, it is impossible for one who is himself sunk in the mire to release another who has fallen into the mire; only he who is himself out of the mire can save another from it. Verily, Cunda, he who is himself not restrained, not disciplined, and not spiritually liberated cannot make others become restrained, disciplined, spiritually liberated and enlightened.” Let us hope that among the growing generation of our Buddhists there will be many individuals who are really self-controlled, subdued or self-tamed, and spiritually liberated and truly enlightened.

But lest any students should despair of once becoming such living witnesses to the Buddha – Dhamma, let me by way of encouraging them conclude this article with yet another quotation from the Word of the Buddha: – “Even as the great ocean (as seen from a sea beach) deepens, gradually, slopes gradually, shelves gradually, with no abruptness like a precipice, even so in the Buddha – Dhamma there is a gradual practice, a gradual training, a gradual course, with no abruptness.” There is no abruptness in attainment of true spiritual insight and liberating knowledge, for the realization of these things is a matter of gradual evolution by repeated conscious efforts.