The people of Myanmar take great pride in their religion, arts and culture. They are predominantly Buddhist (Theravada Buddhism) and being a Maynmar is synonymous with being Buddhist. King Anawrahta, founder of the first Myanmar Empire, brought Buddhism to Myanmar in about 1044 AD and Theravada Buddhism, the national religion, has remained a constant thread in the cultural fabric since the days of Bagan, Buddhist festivals dot the national calendar, while religious observances form a daily pattern repeated at temples throughout the country. Such is the persistence of the faith that virtually every hilltop, no matter how insignificant or remote, is crowned with a gleaming white pagoda and the land itself draws definition from the golden spires of myriad temples.

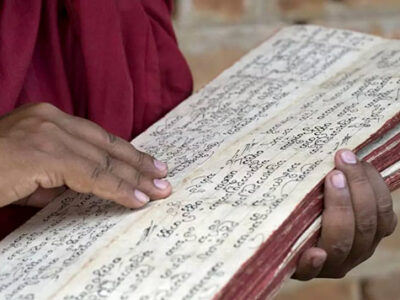

It is also in the Buddhist temple that the Myanmar people give finest expression to their considerable talents in the arts. The architecture itself is distinctive, while dazzling interiors reveal splendid sculpture in the form of glided and painted Buddha images, as well as numerous examples of decorative crafts, from characteristic lacquer ware and silver-work to wood carving genius. At festival times, puppetry, music dance and other performing arts come to the fore.

Myanmar’s greatest claim to pride and fame is the Shwedagon Pagoda, the biggest and most important Buddhist shrine in the entire country, Resting on the top of Singuttara Hill, its golden spire soars nearly 100 metres to dominate all the surrounding area, appearing immovable and timeless.

More than a towering, gleaming wonder, Shwedagon is a religious fairyland. As you reach the top of one of the four covered stairways, you enter a scene of myriad pavilions and shrines of statuary images, of throngs of devotees praying and making offerings. The spirit of the place is almost tangible and you are moved by the sight which, in the words of Somerset Maugham, is “like a sudden hope in the dark night of the soul”.

The Shwedagon dominates Yangon as no other single structure does in any city in the world. The origins of the Shwedagon are shrouded in legend. King Anawrahta, who founded the first Myanmar Empire in Bagan, visited the Shwedagon, and in 1372 King Byinnya U of Bago renovated the Pagoda. Fifty years later, King Biniyagyan raised the stupa to ninety meters. Legend has it that inside the Shwedagon is a treasure trove of eight hairs of Buddha, diamonds, rubles, sapphires and other gems, all buried in the main treasure chamber under the spire. The Shwedagon is not only a remarkable architectural achievement, but also a perfect symbol of the people’s devotion to their national religion.

All important Pagodas in the land celebrate their own festival and the Shwedegon is no exception. Its festival is celebrated during the month of Trabaugh which falls in February and March. It is celebrated at the foot of Singuttara Hill, where all types of festivities are encouraged.

As stated earlier, being a Myanmar is synonymous with being Buddhist and the Myanmars are much concerned with retaining their cultural identity. This extends to their language, dress and behavior. Although most countries in the region have abandoned traditional dress or costume for Western attire, Myanmar is one of the few countries which steadfastly retain its national dress.

Myanmar culture also extends to festivals to commemorate religious and national events. One of the most important is the Thin-gyan, or water festival, which falls in April. Participation in this festival is mainly by young people and children and consists of throwing water on each other to wash away sins and bad luck.

In more prosaic terms, a Bama (Myanmar) summed up the root of his people’s hospitable and easy-going nature by confessing: “we live for festivals and feasting”.

Regardless of often difficult circumstances, the Myanmar expresses and enviable stoicism, and festivals and feasting do, indeed, punctuate their way of life.