On occasion the question is brought up whether the Dhamma is still valid in our time. Some people seem to think that while the Dhamma may have been well suited for the Asia of twenty-five hundred years ago, it has no place in a 90th Century world dominated by fast-placed, aggressive, increasingly amoral Western technology and materialism. Therefore, it should be retired to a museum, to rest amid the musty relics of a vanished Golden Age. In other words, it is as if an age-old system of treatments were no longer useful because the diseases of today are different.

Others approach the problem from another perspective. The efficacy and appropriateness of the Dhamma is not questioned. Instead, the feeling is that modern man does not have the necessary time and opportunity for effective application and practice of the Dhamma. The medicine is right for the disease, but the patient is not able to take advantage of the treatment.

Let us examine both of these views. It is true that the ancient world was a different place from ours. Certainly, life must have been considerably slow-paced, as it is even today in agricultural village societies. In short, the 20th Century Rat-Race, the technology that created it and all that they imply, both good and bad, did not exist.

The underlying problem, the basic problem of the world remains the same no matter how many the exterior trappings may change and that problem is that the world is a place of suffering.

The world is a place of suffering, but the suffering is not in the world. It is in the mind. It is in your mind, and it is in my mind, and it is in the mind of every sentient being in existence. That is, of course, the kind of statement that brings out the critics who insist that Buddhism is pessimistic. Not so, Buddhism impartially states what everyone can see and verify independently for himself.

Let us define suffering. In his first sermon given after His Enlightenment the Buddha said as follows:

“Birth is accompanied by pain; disease is painful; and death is painful. Sorrow, lamentation, grief and despair are suffering. Enduring the unpleasant is suffering and separation from the pleasant is suffering. Not getting what one wants is suffering. Indeed, all the five aggregates which arise from craving and attachment are suffering.”

Who can possibly argue with that statement? Suffering is physical, mental and emotional. And none of us is exempt or immune.

It is true that pleasure and happiness also exist. No one can deny that, either. But pleasure and happiness are fragile and fleeting. They depend on certain conditions being in accord with what we want and expect. As soon as those conditions change (and change they will) as soon as we no longer have things our way, some degree of unhappiness or suffering arises. Be it trivial or severe, it is suffering nonetheless.

We create our own misery and unhappiness, and even determine the degree to which we suffer by the expectations we set up, and by the strength and inflexibility with which we hold those expectations.

We have just restated the first and second of the Four Noble Truths, and all we have said is just as true for us today as it was the day the Buddha first uttered his Teaching. We see that the ancient and contemporary worlds are alike in that both are filled with sentient beings, all of whom are experiencing sufferings and all of whom are seeking relief.

To this suffering the Buddha was no stranger. He saw it clearly all around him and he was sensitive to it. Out of his compassion, he set aside his own life of comfort and privilege in order to find, once and for all time, full and permanent release from the suffering inherent in all conditioned things, situations, and circumstances.

After years of diligent searching, he succeeded in liberating himself. After that attainment of Enlightenment, again out of his great compassion, he spent the remaining forty five years of his life showing the way to liberation to any and all who would listen. The Dhamma, the Teaching of the Buddha, is not his invention any more than the laws of physics are the invention of Isaac Newton. Newton was simply an observer who devoted himself to the investigation of certain laws of nature which he studied, experimented with, described, and brought to the attention of others for the benefit of society. Just so did the Buddha devote himself to finding the cause for the arising of suffering and the means to its cessation.

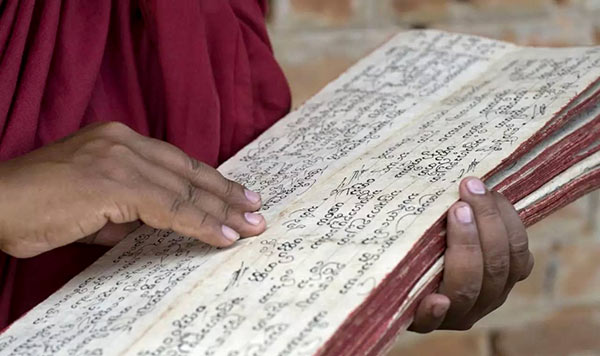

The Dhamma is a summary of the Buddha’s search, discoveries, applications, and results. It is a report of the way the laws of nature and mind operate, and a set of instructions, a manual, as it were, of how each of us can most effectively use that information for our own greatest benefit in all aspects of daily life, and ultimately for his own Liberation from suffering. It is eternally valid.

The first two of the Four Noble Truths serve to identify the problem and to reveal its cause. The Third Noble Truth identifies the remedy and the Fourth Noble Truth is the actual application of the treatment. It is now entirely up to each of us to take it from there. The Buddha did all that he could do. No one could have done more. The doctor can identify the disease and indicate the remedy. But he cannot undergo the treatment on behalf of the patient.

Similarly the Buddha shows us the Path and gives us a detailed map with comprehensive instructions, but each of us must put forth the effort to travel that path in order to reach the goal. No one can travel it for us.

What does it mean to be a Buddhist? What does it entail to follow the Path that the Buddha mapped out for us? Can we do a good job of it (here’s that magic phrase again!) in today’s world?

To be a Buddhist in name only is very easy. It is also a colossal waste of time, a disservice to all practicing Buddhists, and an insult to the Buddha.

To be a serious practicing Buddhist does take time and effort and commitment. One has to take time to study the Dhamma to be well acquainted with the core of the Teaching. One must know the Precepts not just well enough to repeat them, or to do the minimum to “get by”, but to understand in depth their ethical and moral basis. Once a person has this knowledge and understanding and lives by it, he realizes that it is not for one’s spiritual benefit alone, but that it orders and simplifies all of everyday life as well. This includes family, business, and social relationships, child-rearing, in short, all the aspects of the lay householder’s life. And upon this solid foundation, and only upon it, can one build one’s meditative practice, that is, the mental cultivation of insight which leads to Enlightenment.

Yes, it does take time and effort. But all worthwhile endeavors do. And this is the most worthwhile of all, bar none! We find time and energy for all sorts of draining, useless, even harmful pursuits. Certainly we can make time for the application of the Dhamma.

Today, we are extremely fortunate on two counts. The Dhamma has come to the west, and it is well enough known and received that there are large numbers of very good Buddhist books readily available and easily affordable. That was hardly the case two or three decades ago. We are further greatly blessed by the presence in the West of many great monks who have come to offer the Teaching and to establish temples and centres for the study and practice of the Dhamma.

With every passing year, the numbers of monks and centres increase. And there are more and more Western-born monastics and laypersons as well. The tree of Dhamma has been successfully transplanted to the West. It has taken root, and is flourishing. To receive information, training, advice, and support is no longer a nearly impossible task. It is easier than ever.

One further point must be addressed. Many persons seem to feel that in order to make significant progress, one needs to enter the monastic life. That they cannot do so because of lay responsibilities, or because they feel they are not suited for monastic life, appears to them a great obstacle.

The good news is that the layman can make a great deal of progress right where he is. In his present situation, the Suttas abound with accounts of lay women and men who rose to great spiritual heights, even attained Nibbana. And all the while they managed households, raised families; earned livings took care of personal affairs, and operated businesses. To the casual observer they were living very ordinary, normal lives. And this is no less true today.

The Dhamma is unique, a complete training system, unmatched and unsurpassed by any other. It is not difficult to follow. One starts precisely where one is and proceeds at his own proper pace. At the very least, adherence to Buddhist ethics will greatly simplify life, bring peace of mind, and allow one to live a blameless existence. It will also assure a wholesome rebirth in which one may again have the opportunity to continue making progress towards Liberation from Samsara, should one fall abort of Liberation in this life.

The Dhamma is fully as potent now as it ever was. And once we make up our minds to apply its principles to our lives, we shall see that all that needs to be done is well within our capabilities, even in today’s hostile, whirlwind world.