By- Ven. C. Nyanasatta Thera

When a new student of the Dhamma read any book on Buddhism, he wants to know how the Word of the Buddha has been handed down to us all these 2,500 years of the History of Buddhism. All Buddhists and non-Buddhists know that the Enlightened One did not write any of the Dhamma Books we now study. At that time writing down one’s thought and instructions was not the practice, all the discourses of the Master and all the rules for the Order were handed down in the memory of the disciple, whose retentive power was much superior to our own. After the passing of the Teacher the task of teaching the Dhamma fell on those of the chief disciples who knew all the Teachings and rules by heart, learnt either direct from the Master or from other chief disciples who had followed the Perfect One during the 45 years of his career of teaching. From time to time the disciples met at a Council to recite all the Teachings and the Rules, so that nothing should be forgotten or changed. All Buddhists know that on the Full-Moon Day of Vesak (May 17, 1954) commenced and on 23rd of May, 1956 ended the Sixth Great Council at Rangoon in the Union of Burma. In the long history of Buddhism there have been already five Councils for the recital, reading and confirmation of the authentic teachings of the Enlightened One and his great disciples.

- First Council of Rajagaha

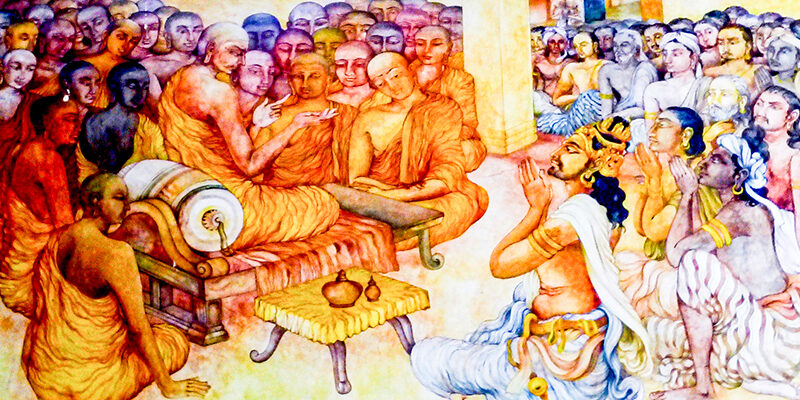

The first Sangayana, or Sangiti as the Councils are called in Pali, took place three months after the passing of the Buddha. According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Digha Nikaya 11.16, Venerable Maha-Kassapa, one of the Great Disciples, while proceeding with his pupils to render the last homage to the 80 years old Master, who was about to part from his disciples, met a certain ascetic, who informed the bhikkhus that the Blessed One had already passed away. When the younger bhikkhus heard the sad news, they began to mourn aloud, being unable to hear the sudden loss of their beloved and adored Teacher. Upon this, the elderly monk Subhadda, who had joined the Order in his advanced age, and hence never had mastered the rules, attempted to console the lamenting junior monks thus: – “Do not grieve, brothers, for now we are definitively released from the restraint of the Great Teacher and his too rigid discipline. While the Master lived, we were constantly rebuked for failing to observe the hard rules; but now we are at liberty to do as we please, therefore do not grieve.”

Hearing these words and reflecting on the possible future decline in the observance of the Law of the Blessed One, Mahakassapa thought of counteracting any such tendency by convening a Council of 500 of the foremost disciples who knew all the rules of the Order and all the discourses of the Master. With the assistance of King Ajasatta, the holy and competent disciples of the Buddha assembled near Rajagaha and chanted during several months the discourses on the doctrine and the rule of discipline of their Master.

In this Council they classified the teachings into groups of related topics of certain length and entrusted the leading scholars among themselves to take charge of the respective collection, or a portion, of the Canon and preserve it in its pristine purity, thus handing on the original teaching to their pupils and pupils’ pupils. Thus the instructions of the Buddha were kept well in the memory of the eminent disciples and, possibly with written records or at least of a table of contents (matika), to assist memory, were handed down through generations of competent teachers in charge of the divisions of the sacred scriptures, until the texts were systematically written down after succeeding Councils. In the course of chanting of the Canon during these Councils the collected scriptures were divided into three main sections, which came to be called ‘receptacles’ or ‘baskets’ or rather ‘caskets’ according to contents, as (1) Discipline, (vinaya), (9) Discourse on the Dhamma (sutta), and (1) Higher doctrine or the systematic analytical exposition of the Buddhist Pilosophy (abhidamma). In course of time, the Three Collections of Texts began to be technically styled, “The Three Baskets”, the “Tipitaka” and the “Three Collections” of the Sacred Scriptures are thus called up to the present day.

It is these same texts, this Tipitaka in the Pali language, that has been recited in Burma, it may be that later generations found it expedient to elaborate further some of the doctrines, add explanations, commentaries on the text, or otherwise embellish with verses the sober tone of the genuine Word of the Buddha. They may have added a new frame giving the occasion for the promulgation of a particular rule or discourse, giving the historic setting, in order to fix it in the memory of the disciples. Edifying stories of miracles and supernatural beings, ‘devas’, may have been included, in order to maintain the interest of lay devotees. But the core of the Scriptures is the very word of the Blessed One, most probably in the Master’s own idiom, the tongue once called Mahadhi (the language of the country called Magadha), now generally known as Pali, whose sonorous tones, even when reproduced by monks who may not always be Saints, fill the audience with a feeling of listening to the Blessed One’s discourses presented by the Master himself.

Intellectual students brought up in the critical Historical Method, rejecting everything that, according to the so-called Higher Criticism, appears a spurious interpolation or corruption, have a perfect right to disregard the later accretions, for Buddhism does not insist on blind belief and acceptance of irrational dogmas. But a note of warning must be sounded to all who are too over-zealous reformer and critics: – “It is well to guard against rejecting, along with the supposed additions, the very Word of the Buddha.” The Word of the Buddha ought to be kept, while the unessential additions, all later accretions, and seemingly irrational stories of the Jatakas (Birth Stories of the Buddha) and Commentaries are not so important. And although these stories may offend some students, that have served their purpose well all the se 2,500 years and hence may be tolerated by all for the sake of their antiquity and moral appeal. In those stories it is the moral that really matters, not the literal reading of the whole story as gospel truth. Perhaps the stories were never taken more than allegorically, and it is only we who are to blame if they appear to us irrational!

- Council of Vesali

The Council of Vesali was arranged a hundred years after the first rehearsal. The occasion for the Second Synod was the decline in the strict observance of the rules for monks. It was at this Council that the practice of accepting or asking for money, carrying salt in a horn in order to improve the taste of the bhikkhus alms food when necessary, and similar offences were condemned as unorthodox. But the too many recalcitrant monks of Vesali, offenders against the Vinaya, seceded, founded a separate Order, alter formed their own Canon of Doctrine and Discipline claiming to teach the Dhamma-vinaya of the Buddha. Out of this little disagreement, which could have been peacefully settled had the Buddha and his great disciples been living, there arose differences in the conceptions of the Dhamma, some fundamental, some unimportant; but in course of time the break became unhealable, and the new trend began to be called the Mahayana.

- Council at Pataliputta – Patna

The Third Council at Pataliputta (Modern Patna), under the patronage of the Buddhist King Asoka, is important for its decision to send missions as far as Ceylon and many other far and near lands to teach the Dhamma there. Ceylon was especially fortunate in thus obtaining a Royal “Envoy of the Truth”, a “dhammaduta”, in the person of the great Mahinda, son of King Asoka, and a few years later another royal mission with another Saint, the Nun Sanghamitta, daughter of King Asoka.

Thought the Third Council of Pataliputta had been splendid success in purifying the Dhamma and propagating it in so many distant lands, it had also the effect on the dissenting Bhikkhus, that their being once more condemned and expelled from the Order only increased their dislike for the orthodox Theravada Bhikkhus. It strikes one that instead of giving instruction in the true Dhamma – vinaya to the erring members after a sympathetic hearing of their reasons for not being able to obey the rules in fact instead of taking up a more conciliatory attitude to those who thus erred and offended, the Elders imply condemned and expelled all troublesome monks. Purge seems much easier than prevention and amicable settlement of differences. Perhaps the task of re-educating, by giving a ‘Refresher Course’ to the many thousands of ‘non conformists’ was really beyond the power of the Elders, and the dissenters must have refused any instruction and advice. This unrelenting expulsion of the offenders was done with the good intention of perpetuating the pure Dhamma – vinaya; but when we now read the uncomplimentary references to ‘Hinayana’ the ‘Lesser Career’, by its opponents; we feel that much could have been done in those far off days to prevent this bitter hostility.

- Great Council of Lanka, at Aluvihara in Ceylon

The Fourth Council in Ceylon, 29 B.C. during the reign of Kind Vattagamani Abhaya is famous, for it was then that the whole of the recited Scriptures was systematically written down on permanent material, with all the detailed classifications that now obtain in the Pali Tipitaka of the Theravada School. Some scholars do not count the Ceylon Council as the Fourth but refer instead to a fourth Council under the Kushan King Kanisha in North India, when the celebrated champion of the Mahayana met to fix their own Canon. As this is an article on Theravada Buddhism of the Pali Scriptures, and a portion of a Practical Course in Buddhism, it is outside our scope to deal with this Council. As the opposing camp except the Sarawastivadins never possessed a complete Canon similar to the Pali Tipitaka, the aims of the Kanishka Council were quite different from those of our Sangayanas. The Theravada Councils did not produce a ‘Council Version of the Dhamma’ but only confirmed the Scriptures recited, not composed, at the Sangayana.

- Council of Mandalay in Burma

The Fifty Sangayana at Mandalay, upper Burma, in 1871, when the British were preparing to occupy the whole country, has the unique distinction that the whole Pali Tipitaka was then engraved on 729 slabs, of marble. This great work was achieved at the command of King Mindon. It seems as if the pious monarch had anticipated the invasion of his domain and thus wanted to prevent the disappearance of the Dhamma, in case all the other books of paper and palm leaf shouldbe burned by the invader. All the 729 marble slabs bearing the Word of the Buddha were enshrined in a Pagoda, and they can be seen up to our day in the city of the Fifth Council. Though this act of piety did not ward off the imminent occupation of the King’s country, the presence of this great number of slab-books of the Tipitaka must have been a source of consolation and inspiration in the dark days when Kings no more protected the Dhamma in Burma.

- The Sixth Great Council of Burma

The Sixth Great Council in Rangoon (1954-1955) used in its preparation of the Texts these same marble slab – books, comparing the old version with printed Pali books now extant in Burma, Ceylon, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, India and even the Roman script of the critical editions of the Pali Text Society of London.

After several years of preliminary work of collating, correcting and amending the faulty passages – for mistakes are bound to appear in the texts when anyone was permitted to copy the books for new editions – consulting the greatest authorities on what is the most probable correct spelling of the diverging wording or reading. The Sangayana proper opened on 17th May, 1954, in the artificially built Rock Cave, specially constructed for this purpose a little distance from Rangoon. The chanting of the Tipitaka is now completed and the approved texts are printed. A modern printing press has been installed in a separate building near the Sacred Cave, and there the approved texts were printed as soon as they had received the necessary sanction by chanting. 2,500 of the most erudite bhikkhus, in relays of more than five hundred at a time, had during these two years solemnly chanted, or recited, all the books of the Tipitaka in the vast hall built as a cave, for it was in a pavilion in front of a cave near Rajagaha that the first Sangayana was held.

The opening and the closing sessions of this Buddhist Synod were attended by members of the Buddhist Order of Monks of the whole Theravada Buddhist world and even by the high-ranking dignitaries of the Mahayana Order of Monks and Priest of Japan, China, Vietnam and Malaya. Had there been no Iron Curtains at that time, even representatives of Tibet and the other trans-Himalayan lands would have appeared at this truly World Council of the Buddhists. It was for the first time in the long history of Buddhism that Western Bhikkhus, namely the German Elders, were seen at a Sangayana, if we assume that the ‘Yona or Yavana’ bhkkhus of Asoka’s time Council were more like Asiatic than Europeans from India in Greece. It is expected that after this Council the Buddhist Envoys of the ‘Dhammadutas’ will go to many more countries than those reached by Asoka’s missions. At that time only the near Asian countries and the Mediterranean lands were reached: now all the continents of the word world will be able to receive the Message of the Enlightened One, either in books or from highly qualified and competent members of the Order of Bhikkhus. In Germany, for instance, they plan next month for higher Ordinations on German soil, of the sons of the soil, to mark the year 2,500 after the passing away of the Buddha.

In order to render full justice to the Sinhalese Buddhists, it must be mentioned here that a Sangayana on a smaller scale has been taking place all these past 5-6 years at the Oriental College Vidyalankara Pirivena, Kelaniya near Colombo. This Council intends to publish the Tipitaka in Ceylon as soon as the sessions are completed. Thus the Sinhalese will contribute to the celebrations of the 2,500 Years Anniversary of Buddhism that are to commence soon. The Government of Ceylon has contributed five millions or more towards the celebrations, and will give more when need arise; the public will spend lavishly in order to manifest their faith in the Dhamma. The Buddhists believe that the Buddha-Dhamma will be practiced for another period of 2,500 years, hence all these Councils are expected to unite the Buddhists, create consistency in the Tipitaka, and thus to secure the practice of the Buddha-Dhamma for a long time to come.